This is Blog Post submitted by Bill Traynor and Frankie Blackburn to the Knight Foundation. A reflection on a convening of community Network Builders that Bill and Frankie co-organized and led in Miami in November of this year.

This is Blog Post submitted by Bill Traynor and Frankie Blackburn to the Knight Foundation. A reflection on a convening of community Network Builders that Bill and Frankie co-organized and led in Miami in November of this year.

Community Network Building Convening – Miami 2011

Blog Post for Knight Foundation by

Bill Traynor and Frankie Blackburn

25 senior Community Network Builders’ from around the country converged in Miami this past fall to talk about their work in an effort to generate what they called “actionable knowledge” about what they do, how they do it and why they think this work is distinctive and impactful and needed now, in struggling American communities. Invited by the Knight Foundation and Grassroots Grantmakers, with our help and facilitation, the convening was designed to engage each participant as BOTH a practitioner and a ‘thought leader” in the field.

Five headlines emerged from what we consider a first ever gathering of this type:

- Our primary intervention is to create, protect and preserve intentional community spaces in our local areas for connection and co-investment.

- Well designed and effectively stewarded spaces unleash significant capacity for creative local solutions and cultivate important new connections across class, ethnic and racial, geographic and generational divides.

- As stewards of these intentional spaces, we must fully inhabit these spaces, expose our own questions and vulnerabilities and work to diminish the impact of positional power on the co-investment process.

- The organizational forms needed to support this work must be more flexible, less boundaried and more adaptable than traditional community-based organizations.

- The case for supporting community network building is clear to practitioners, but needs a relationship-based approach to engaging funders, policy makers and others in co-creating a data/narrative for external case making.

There was consensus that this is an intervention with a strong bias. The bias is that there is a lot more value and power to build on in poor struggling communities than is recognized by most community development, community building or social service interventions. But this power and value is locked up or unrealized because the spaces that these interventions create are not designed to genuinely explore, reveal and then put to use what people have to offer each other and their community. Sometime they say they are and sometimes they try to be. But community network builders would say it doesn’t take much to miss the mark, but when you miss it you miss it by a mile.

Each of us knows instinctively the community spaces where we are welcome and where we are not….. when we are genuinely needed and when we are not….when we are genuinely recognized and when we are not. And none of us spend more time than we have to in spaces where we are not welcome, not needed and not recognized.

While the Community Network Builders at the Miami convening can be found working in a range of disciplines – community organizing, community building, human services support, engagement in faith communities, health care – they have a common perspective and a common approach: to offer the optimum environment for people to engage, bring their own best stuff, build trusting relationships and co-create.

Over the two days, participants – organized beforehand into Session Teams – led Open Space small groups discussions and fish-bowl reflections sessions around 4 areas of inquiry:

- Practice: What are the distinctive elements of network building practice at the local level?

- Leadership and Stewardship: What is needed from us to lead and guide these efforts?

- The Forms: What are the new organizational issues/challenges that arise in network building?

- Case Making: What is the case for this work and how do we make it?

Here are some key conversations:

The Practice and Urgency of Creating Space

Community Network Leaders see their practice as creating aspiration-driven spaces – rooms, meetings, physical space, moments of community life – that help people connect across differences, build supportive relationships, engage in value exchange, generate action and co-create with each other. They see their work in these spaces, wherever they may be, is rooted in an essential bundle of activities and behaviors explicitly designed to create the force needed in the moment.

- A Connecting Force – sparking deeper relationship building within existing networks and bringing organic networks of people together across differences

- An Affirming Force – helping people explore, reveal and exchange actual value

- A Flattening Force – challenging and neutralizing positional power dynamics derived from professionalism, race and class so that those sharing the space can engage as ‘people first’.

- A Revealing Force – providing the time and opportunity to engage in learning and exploration, around issues, neighborhood life, life skills

- A Generative Force – facilitating the time and space for organic generation of new campaigns, movements, collaboration, new community institutions and organizations

In these kinds of spaces, a community can re-discover its functionality and power. Some of these spaces exist but there are nowhere near enough of them to constitute the ‘connectivity infrastructure’ that is needed in today’s world. There needs to be a concerted, intentional and strategic effort to generate these spaces. If today we have 10 such spaces, tomorrow we need to have a hundred and the day after that a thousand. A community that is populated with this kind of connectivity infrastructure will have a higher degree of self-determination, will be able to do lots more with the less they are left with, will be populated by more people who have a actionable sense of their own power, and will have the aggregate and collective power to stand up for itself in a regional and global economy.

As Leaders and Stewards, Trading Control for Co-Investment

It is a challenging irony that to effectively lead in a network environment requires one to lead with one’s own needs, questions and vulnerabilities. Community Network Builders see their primary role as ‘creating, recognizing and protecting spaces for co-investment.’ But the leadership/stewardship role in a network like this creates a fundamental challenge to the leader – to work to diminish his/her own real and perceived positional power in order to create space for others to lead, create and engage. This is more than leading by example. This is the primary set of acts and behaviors that is the leverage to pry open spaces where trust can be established and rule. Community Network Builders work in environments where mistrust is heightened and the pain of being invisible and diminished is palpable and present in many people and therefor in most of our interactions. It takes radical acts of surrender to counteract these forces and we as leaders need to surrender first; surrender control, pre-conceived notions about what will work, pre-determined views about the outcomes that will result.

If surrender is the first role, bold experimentation with “devices and contrivances” designed to bring people into mutually supportive relationships is the second. The network steward is not a passive facilitator but the first in the room that voices the need and desire for new connections and relationships and the ‘mad scientist’ who comes up with contrivances like The NeighborCircle, the NeighborNight, Tuesday’s Together, The Check In, the Hello Circle, Speed Friending, The Weaver Explore – all simple devices to encourage connectivity across differences.

The 3rd primary role is to protect this kind of ‘connectivity space’ when the network is successful and gets busy producing the programs and projects and campaigns that inevitably and quickly grow from all that great connectivity. The need for these spaces does not diminish with network growth, but the ability to protect and sustain them becomes more challenging and complex.

In each of these roles, there are essential acts and behaviors that need to be performed and proliferated though the network environment. Some of those featured are:

- Inhabiting the Space – Being intimately engaged at all levels of network functioning. Don’t lead from the outside.

- Helping people name power, power relationships and power driven dynamics that usually drive decision-making and outcomes in other community spaces and get in the way of genuine co-investment

- Introducing and reinforcing network-centric, and relationship strengthening practices

- Magnifying and raising the profile of positive norms and outcomes when and where they emerge

Forms Designed to Bridge Different Worlds

Local network building is challenging traditional ideas about community based organizations and blurring some lines between and among silos and the helping professions.

Because the orientation is to work through networks of relationships, the forms that are emerging to support this work are needing to be more flexible, less boundaried and exceedingly adaptable.

Because they are challenged to create shared spaces – shared by people and organizations that have not and would not typically share space – they are pushed to cross traditional neighborhood boundaries, professional boundaries and institutional boundaries.

In addition, local community networks have three unique features that also challenge traditional forms:

- Networks don’t occupy the same kind of institutional space in local communities as CBOs, principally because they represent different layers of community life. In fact, participants described community networks as layers of connected relationships – much like a lasagna – that can lay on top of each other without getting in each other’s way. The way that one can be a member of a health club and a church and a buying club and a sewing club – picking and choosing which to be invested in in a given week, this is the kind of layer the community network represents – “the connecting with other local community members club. “ It was felt that far from competing with local block clubs, associations and CBO, a healthy community network can feed these forms with engagement, expanded networks, and people who are more informed and more skilled in effective participation.

- Community Network Building works to identify and support and sustain natural networks in neighborhoods while challenging them to cross lines of difference – to bridge. This is a challenge but also an opportunity to create new functionality in divided communities. This work is not about getting institutions to collaborate but rather about a careful cross stitching of individual relationships that are ‘surprising’ and that begin to weave networks that wouldn’t otherwise be weaved. Intergenerational, cross professional, neighborhood residents and leaders of large institutions, and of course cross ethnic and racial.

- Networks also generate infrastructure for aggregate power in addition to collective power. Networks are best at offering many options for many people – all loosely linked together. Some of the new community organizing campaigns cited by community network builders were focused more on creating a kind of ‘market demand’ for change rather than traditional community organizing collective demand. During the convening we called this “aggregate power” which is more akin to voting or consumer purchase power than it is to constituent based advocacy.

These and other dynamics are shifting the way that Community Network Builders are crafting the infrastructure – funding, staffing, internal management needs, technology needs – that they require to cultivate local network development.

The Griot’s Role in Community Network Building

The word “Griot”- the traditional name of the West African storyteller – comes from French and Portugese words for “servant.” The Griot’s role is to hold and pass on the powerful narratives that guide moral choices and community life. The Griot is a servant of ‘the truth.” Capturing and disseminating the truth about the impact of Community Network Building remains a difficult challenge for a number of reasons but the conversation at the Miami Convening was hopeful and instructive. First, because we all realized that we need our own version of the Griot – a network of people from a range of disciplines who work together as servants of the truth and tell the powerful story that is emerging from this work. There are 4 elements to this powerful story that can be developed:

- Effectively Capturing the Tangible Outcomes – what are the raw programmatic and/or community building outcomes that spring from this work.

- Finding and Unleashing powerful voices who can testify about ‘Life Inside the Network’ – the infrastructure for ‘bringing to life’ the essence of the network experience is still out of reach. Powerful nuanced stories require strong storytelling skill and broadcast medium. These elements are needed.

- Proving Differential Outcomes: Being able to illustrate the “net value” of the network environment to programmatic and other outcomes through indicators like retention, effective use of resources, leverage, mutual support and so on

- Convincingly describe the Paradigm Shift; developing the language and imagery needed to make a compelling and clear distinction between Community Network Building and other interventions.

Given the newness of this work and the few resources that have been dedicated to developing the practice, the challenge today lie in capturing the essence and importance of “a good spring season” of turning soil and sowing seed – always hard to truly measure until the harvest.

But, as the group agreed, it’s all about telling a powerful story: having a powerful narrative that is backed by powerful evidence, some of which can be/should be quantitative data. But the task is not a narrow one of being able to identify and commit to a data set and tracking technology. The task is to generate a broad partnership willing to work closely to develop and disseminate a powerful narrative in an environment characterized by skepticism, a short term outcome orientation, and an unwillingness to commit the resources needed to do this well. This will take relationship building across lines of difference between and among a special group of people who occupy the “practitioner, funder, policy maker, evaluator” spaces, but who are all willing champions and, even more importantly, willing to be Griot’s in their own complex and rarified environments.

These are just some of the thoughts and knowledge that emerged from our convening that we know are driving action today in communities around the country. There are great notes, graphic illustrations and video and photos available that bring our moment in Miami to life as well. There are new connections and new trusted relationships among experienced community builders that were started during our convening that will bear fruit for years to come. There is energy and there are strategies for continuing the network building we began in Miami – with cross city learning, regular group Skypes and conferencing and further convenings. All of these things will be pursued in a network-centric way: demand driven and with shared leadership.

We are often pressed for the “elevator speech” around this work. We don’t have that. But because community network building is about engagement and conversation, we conclude this piece with an “elevator conversation” that we could imagine taking place once we have engaged (trapped) a foundation leader, corporate CEO or policy maker in an elevator that gets stuck for a little while on the way up to the 50th floor. Does that work? J

How can I/we best spark change in my neighborhood?

- Create a community network where lots of community members can get active and connect with others across lines of difference.

Why is this strategy the best answer?

- Times are tough, our communities need positive change and we need all of our members to be doing well and contributing to community life. But today there are not nearly enough positive ways to engage. A community network brings people with different backgrounds, perspectives and gifts together to build trusted relationships and to shape and implement visions of change, be they small or large.

How do I/we develop a community network?

- Networks need spaces where people can connect and spark new ideas and action. Community network builders focus on finding and create lots of different spaces (indoor and outdoor places, gatherings, meet ups) that are welcoming to a wide range of people and that facilitate relationship building, mutual exchange of value, learning and co-investment

How do I know if I am creating a good network space?

- People come. People come back. There is a steady influx of new people coming. New ideas for action and connection emerge. There is no one leader. Responsibilities and roles change and are shared. Relationship-building and exchange traditions/protocols that get established. People begin to steward/manage the space themselves.

What does this take?

- A diverse team of people to create the space and do the inviting.

- A carefully crafted invitation to draw people into the space.

- An intentional effort to ensure that the space is comfortable and engaging

- A clear invitation to come back to the space and help manage it

What do we do in these spaces, as they evolve?

- Help people connect and exchange information and opportunity and spark action

- Involve those who come in to help in creating, protecting and preserving the space going forward.

- Create new and better ways to share power and leadership and welcome new people in

- Help people turn their ideas into new community organizations, campaigns, programs and interventions

- Create a forum for deep, thoughtful conversation based on real information

- Actively listen to and capture all of the stories flowing from the exchanges, using them to shape and share a collective narrative for the others to see.

- Embrace all sparks – be they conflict or innovation – and help others use sparks to make the space better or create new spaces.

- Support and hold others accountable for actions flowing from an exchange or a series of exchanges.

- Resist attempts to convert the space into a form that will no longer be welcoming to new people or facilitate mutual exchange.

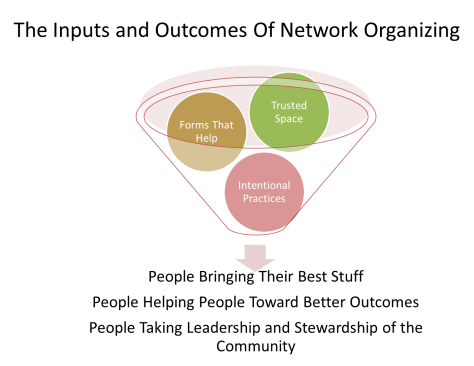

In a recent presentation to the Ways and Means Staff of The Community Builders, we discussed the primary inputs and resulting added value that the Network Organizing practice can bring to a service environment. This slide captures the essence of this. That in any service environment, if we can design Spaces that welcome and feed aspirations, Forms that encourage people to engage in reciprocity (mutual-support) and Practices that help people connect over differences, then we will see important added value in 3 areas: People showing up with their best stuff – energy, commitment, helpfulness and generosity. People helping other people achieve the outcomes that we all want. And people contributing as co-creators, leaders and stewards of the environment that we are creating.

In a recent presentation to the Ways and Means Staff of The Community Builders, we discussed the primary inputs and resulting added value that the Network Organizing practice can bring to a service environment. This slide captures the essence of this. That in any service environment, if we can design Spaces that welcome and feed aspirations, Forms that encourage people to engage in reciprocity (mutual-support) and Practices that help people connect over differences, then we will see important added value in 3 areas: People showing up with their best stuff – energy, commitment, helpfulness and generosity. People helping other people achieve the outcomes that we all want. And people contributing as co-creators, leaders and stewards of the environment that we are creating.

LAWRENCE — In this mill city’s ongoing quest to preserve its history and spark an economic renaissance, one constant has been

LAWRENCE — In this mill city’s ongoing quest to preserve its history and spark an economic renaissance, one constant has been